Senegal’s new law on Public Private Partnerships

Published:Senegal’s law no. 2021-23 dated 2 March 2021 on public-private partnership (“PPP”) contracts (the “New PPP Law”) was published on 15 March 2021 in the Official Gazette.

The New PPP Law repeals law no. 2014-09 dated 20 February 2014 (the “Former PPP Law”) and its implementing decree no. 2015-386 dated 20 March 2015.

Trinity has a significant interest in Senegal having worked on, and is currently advising, a number of projects including various sponsors on solar and captive power projects. Trinity is also working with a lender in relation to rural water production and distribution. The adoption of Senegal’s new law on PPPs has, therefore been closely followed.

The New PPP Law is drafted in relatively broad terms, defining general principles to establish an umbrella framework for PPP projects within Senegal.

The New PPP Law represents a conscious move by the Government of Senegal to create a robust, modern, and comprehensive PPP regime. In particular, it extends the PPP legal regime to public service delegations, revamps the PPP institutional framework, strengthens communication and cooperation between contracting authorities and private investors, and introduces new measures to foster private sector participation, specifically Senegalese and WAEMU[1] companies.

The New PPP Law is part of Senegal’s post Covid-19 recovery plan, aimed at bolstering the country’s infrastructure development need in various sectors such as energy, water, transportation, social housing and health care.

Given the significant role that PPPs can play in developing new infrastructure, the New PPP Law shares similar goals with those of the Former PPP Law, such as:

- strengthening the participation of the Senegalese private sector in PPPs;

- broadening the scope of application of the PPP legal regime;

- providing incentives for companies from the WAEMU zone;

- encouraging unsolicited projects and stakeholders; and

- establishing supporting bodies for the implementation of PPPs.

Despite sharing similar objectives, the New PPP Law adopts different solutions to the Former PPP Law in order to achieve such objectives.

1. Application and Scope

The New PPP Law unifies the legal framework for public service delegations and PPP contracts. Whilst the Former PPP Law only applied to government-paid PPP contracts, the New PPP Law covers both government-paid PPP contracts and user-paid PPP contracts (which include concession, affermage, and régie intéressée).

However the New PPP Law still excludes from its scope, certain regulated sectors (such as the energy, mining, and telecommunications sectors) and some specific contracts, for instance those relating to defence or national security or those relating to the privatisation or transfer of assets of the contracting authorities.

However, it is worth noting that in order to make better use of public funds, the New PPP Law narrows the list of circumstances under which a government-paid PPP contract may be used. A contracting authority may only use a government-paid PPP contract if either the complexity or the characteristics of the project require it. Urgency is no longer a circumstance justifying entering into a government-paid PPP contract.

The New PPP Law applies to PPP projects for which a call for tender has been published after 15 March 2021. PPP contracts entered into prior to 15 March 2021 will remain governed by the Former PPP Law but may only be extended or renewed in accordance with provisions of the New PPP Law (unless otherwise provided for in the contract itself).

2. Simplified PPP Institutional Framework

The New PPP Law simplifies the existing PPP institutional framework via the establishment of key bodies. These include:

- the National PPP Support Unit (Unité nationale d’appui aux partenariats public-privé, “UNAPP”) which replaces the Infrastructure Council (Conseil des infrastructures). This body is conceived as being the technical arm of contracting authorities, mandated to monitor the portfolio of PPP projects, assess PPP proposals, and provide expertise in identifying, preparing, negotiating and auditing PPP projects.

- the Inter-ministerial Committee (Comité interministériel) is made up of representatives from several ministries and is mainly responsible for authorising contracting authorities to initiate procurement procedures for PPP projects.

- a priori Control Body, which will carry an a priori review of the procurement procedures for PPP projects.

- a Regulation and Dispute Resolution Body, which is tasked with ensuring effective coordination with the regulatory authority whenever a PPP is implemented in a regulated sector and dispute resolution in relation to the award and performance of PPP contracts.

- a PPP Support Fund, replacing the Comité national d’appui aux partenariats public-privé, which will further foster PPP projects in Senegal by providing support and funding to PPP projects, which may lack the necessary resources to be launched.

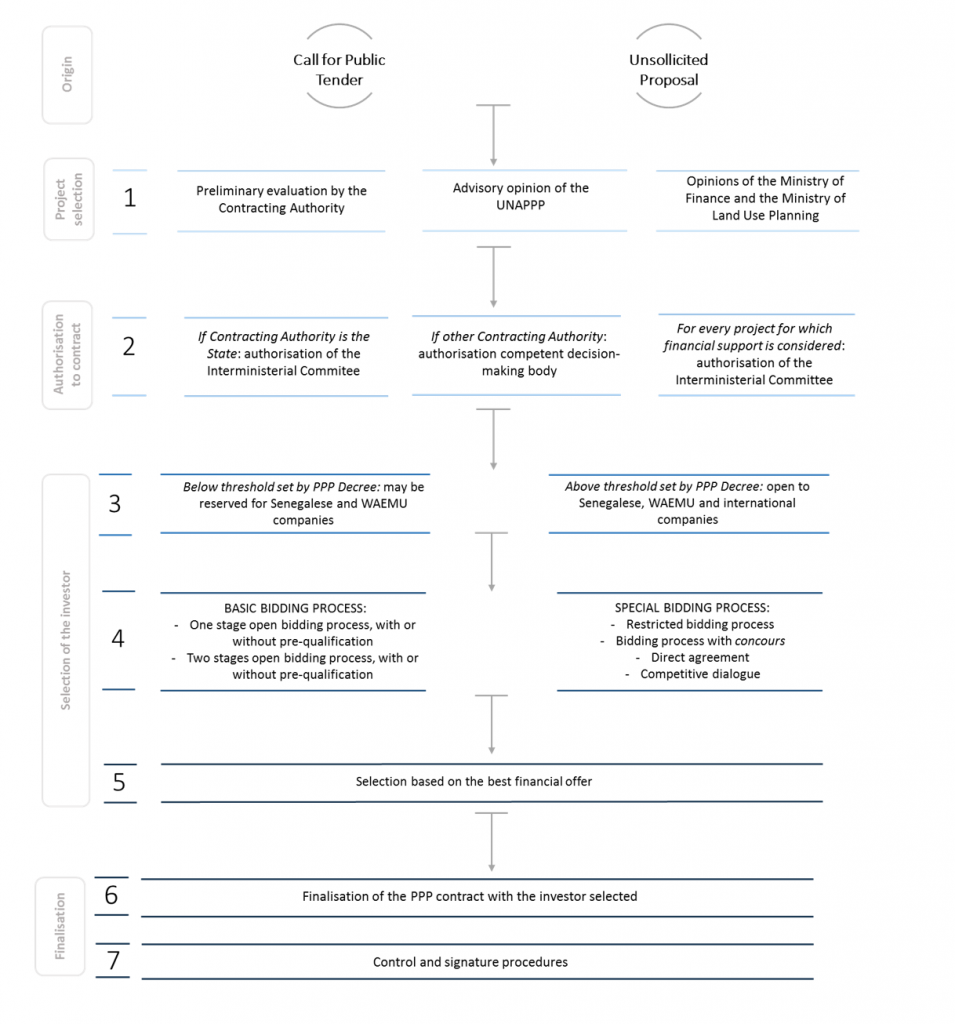

3. General principles applicable to PPP procurement process

The New PPP Law also clarifies general principles that any PPP contract procurement process should comply with, in line with international best practice. Such general principles will be further detailed in the implementing decrees.

3.1. Preliminary assessment

The New PPP Law requires the contracting authority to carry out a preliminary assessment, in order to assess the complexity of the project, the financial and legal arrangements, the allocation of risks and level of profits and sustainable development considerations.

The UNAPP is also required to give an advisory opinion, as part of the initial steps. The UNAPP’s advisory opinion is supplemented by the opinion of the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Land Use Planning on the impact of the project.

3.2. Authorization to initiate PPP procurement procedures

Prior authorisation is required before the initiation of any PPP procurement procedures in accordance with the following:

- authorization needs to be issued by the deliberative body of the local authority if the PPP project is carried out by a contracting authority other than the State; and

- the authorization needs to be issued by the Inter-ministerial Committee if the PPP project is carried out by the State or if the project requires financial support or a guarantee from the State.

It is unclear whether the latter authorisation should be obtained in addition to the authorisation issued by the deliberative body of the local authority.

However, no authorization is required for PPP projects for which the aggregate value is below a certain threshold (such threshold to be defined in the implementing decree).

3.3. Award of PPP contracts

The New PPP Law introduces two new award procedures for the selection of investors – the competitive bidding procedure and the competitive dialogue procedure (in addition to the existing four procedures). Therefore, under the New PPP Law, the award of PPP contracts can be subject to up to six different procedures, either two ordinary procedures or four derogatory procedures, as follows:

- Ordinary procedures

- One stage open tender with or without prequalification; or

- Two stages open tender with or without prequalification,

- Derogatory procedures, subject to the approval of the Inter-ministerial Committee and the a priori Control Body:

- Restricted tender;

- Competitive bidding procedure (concours);

- Competitive dialogue procedure; and

- Direct agreement.

4. Unsolicited PPP projects

The New PPP Law allows private investors to submit an unsolicited PPP proposal to contracting authorities. If the PPP proposal addresses the contracting authorities’ needs, the latter may decide to proceed with a preliminary assessment of the project. The implementing decree will specify under what circumstances the contracting authority may pursue direct negotiations with the investor or initiate a public tender.

While the drafter of the New PPP Law considers the unsolicited proposal to be an innovation, the Former PPP Law already provided for a similar concept. It is therefore necessary to wait for the publication of the implementing decrees to understand the scope of this new mechanism.

5. Electronic communications

The New PPP Law introduces the possibility of communicating and exchanging information electronically.

6. Local content

The New PPP Law introduces several provisions to increase the economic benefits Senegal derives from PPP projects. Such provisions include:

- contracting authorities may include local content components in the tender allocation criteria, such as employment and professional training, reliance on local tradesmen and small and medium-sized companies and sustainable development undertakings;

- PPP projects below the monetary threshold specified in the implementing decrees may be reserved to Senegalese or WAEMU companies;

- the project company shall be incorporated in Senegal and shall be partially owned by Senegalese nationals. The threshold for reserved shareholding should be set out in the implementing decree. (By way of comparison, the Former PPP Law required a 20% local shareholding); and

- Senegalese or WAEMU companies shall be given priority for being entitled to subcontracting operations.

7. Prequalification of investors under a framework agreement

Contracting authorities will now be able to pre-qualify investors under a framework agreement for PPP projects with similar purposes and characteristics. Such framework agreements shall not exceed four years. Specific rules for these framework agreements will be set out in the implementing decrees.

8. Securities and lenders’ rights

Although already a requirement of international project lenders, the New PPP Law clarifies the possibility for lenders to take security over the assets acquired under the PPP contract or to pledge the proceeds and receivables from the PPP contract, subject however to both legal and regulatory provision and the authorization of the contracting authority.

However, the New PPP Law remains silent on the ability for the project company to grant security over land use rights.

The New PPP Law also introduces the right for contracting authorities or the State to enter into direct agreements with banks and financial institutions.

Although the Former PPP Law already included a reference to step-in rights, the New PPP Law confirms the possibility of transferring all or part of the PPP project to lenders or to a third party designated by them, provided however, that such transferee has the necessary financial, technical and legal capacity and, as the case may be, is able to ensure continuity of service and equal treatment among users.

Such clarifications on lenders’ rights should be welcomed by the international lending community.

9. Contract duration

The New PPP Law expands the list of criteria used for determining the duration of the PPP contracts. In addition to the amortization period and the financing arrangements, the New PPP Law provides that the duration of the PPP contract may be determined taking into account the nature of the services and the time required to achieve performance goals.

10. Summary

The New PPP Law introduces significant changes in the approach to the implementation of PPP projects in Senegal. The reorganization of the institutional framework, simplification of the authorization processes, and clarification of lenders’ rights will likely be seen favourably by investors and the financing community.

However, the enactment of implementing decrees will be scrutinised by stakeholders for additional guidance on the New PPP Laws and the practical implementation of its provisions. Arguably, the most anticipated additional details relate to PPP procurement processes and PPP contract mandatory provisions. In its press release[2], the Ministry of Economy, Planning, and Cooperation promised that the implementing decrees will be issued shortly.

Please see below a diagram summarizing the main steps for the implementation of PPP projects in Senegal.

Main steps of implementation of a PPP project in Senegal

Authors: Pierre Bernheim and Béatrice Huon

[1]Members of the West African Economic and Monetary Union are Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo.

[2]https://www.economie.gouv.sn/index.php/fr/articles/22-02-2021/lassemblee-nationale-adopte-une-nouvelle-loi-sur-les-contrats-de-partenariat.